NeoPsychedelia & High Frontiers: Memes Leading To MONDO 2000 (MONDO 2000 History Project Entry #21)

“The rising popularity of MDMA and other designer psychedelics. The developing scene around intelligence drugs and nutrients. The psychedelic roots of Apple computers. The psychedelic garage rock phenomena that was mostly focused in L.A. Even recent releases by Prince and Talking Heads…”

Yet another excerpt from the upcoming book, Use Your Hallucinations: Mondo 2000 in the Late 20th Century Cyberculture.

R.U. Sirius (early 1985: I had come to San Francisco to start the neopsychedelic movement. And even before the first issue of High Frontiers went to press, I heard that there was a new psychedelic rock movement afoot. Some bands were emulating the style of ‘60s garage psychedelia — stuff like The Seeds, 13th Floor Elevator, Blues Magoos, Electric Prunes. The beginnings of this scene had been labeled “the Paisley Underground.†I read that an L.A. band called The Three O’Clock was sort of rising to the top of the scene so I bought their record, disliked it, and gave it a bad review in that first issue — comparing it unfavorably to what I considered smart psychedelic music — stuff you’d actually want to listen to while tripping like Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy by Brian Eno or The Clones of Dr. Funkenstein by Parliament Funkadelic. Not that I was averse to… if you will… exploiting every pop cultural indicator of the coming of neopsychedelia in my quest.

And, with the release of issue #2 of High Frontiers, we had a calling card worthy of some media attention. We (mostly Lord Nose and myself) started promoting the idea that there was a “neopsychedelic†resurgence going on. Several journalists and media outlets took the bait.

We (well, mostly me) gave them a kitchen sink of evidence that something novel was afoot. The rising popularity of MDMA and other designer psychedelics. The developing scene around intelligence drugs and nutrients. The psychedelic roots of Apple computers. The psychedelic garage rock phenomena that was mostly focused in L.A. Even recent releases by Prince and Talking Heads; a sudden plethora of trippy MTV videos; and the playful, upbeat, sci fi, expansive themes running through the new wave radio stations from bands like the B52s and The Thompson Twins (Yes, I would even employ such dribble as the Thompson Twins in my plot for world mutation), we told them, indicated a developing shift in the zeitgeist. Lord Nose would add a note of earnest shamanic gravitas to my pop culture spinnings and, all together, it worked.

We got coverage in San Francisco’s leftist weekly, Bay Guardian and an article by Laura Frasier for the wire service PNS wound up in several daily papers, including Long Island’s main outlet, Newsday (Laura would become a friend and, for a while, Lord Nose’s lover). There were even still more outlets, long forgotten. It was our first small flurry. The viral meme, “neopsychedelia,†was injected into the body politic.

We decided to throw a giant party for the issue and the new psychedelia in San Francisco.  Tongue firmly piercing cheek, Lord Nose came up with the idea to call it the Neopsychedelic Cotillion Ball. No doubt, he was having a bit of a giggle at the expense of Alison’s upper crust breeding and quasi-Victorian stylings — as she was replacing Mau Mau as the third dominant figure in our little karass and — at the same time — playing with Ken Kesey’s famous “Acid Test Graduation Party†that had spelled the end of the Merry Prankster era. We secured this wonderful large venue called “The Farm†and started contacting bands and speakers to see who would appear… for free…

Somerset Mau Mau: I didn’t have much to do with that.

R.U. Sirius: Mau Mau and X knocked on the door at Alison’s house one day to complain about the naming of the Neopsychedelic Cotillion. They said it was alienating to acid veterans in the Haight and hardcore street mutants in general . It sounded too bourgeois. I found that bizarre, given that these guys over in Marin were even more relentlessly absurdist than we were, that they would have taken the title sort of literally.

We got an incredibly positive response when we asked people to perform for us. We had 5 or 6 popular local bands, including The Morlocks, who were the kings of the local garage psych thing. They were like 10 years old (Ok, maybe like 19). . And we set up panels on quantum physics and psychedelic drugs and maybe a few other things. Wavy Gravy agreed to MC. The freakin’ voice of Woodstock for our neopsychedelic rally!

Lord Nose and I went to see Wavy at his famous Hog Farm house in Berkeley to ask him to MC. It was the first time I’d ever been there. He had the Big Pink cover on his bedroom door. His bedroom door was kind of a collage of all sorts of memorabilia of the counterculture and the Grateful Dead, but that 11†x 17†thing dominated. (When I saw him a few years ago, he told me it was still there.)

About a week before the event, I was invited to appear on the Michael Krasny Show on KGO. Two hours long, on Sunday night, it was the Bay Area’s biggest talk radio show and I was going to be the only guest. I woke up that morning with a monstrous cold — cough, fever, the whole package. Early that evening, I downed a triple dose of cough medicine and hit the BART from Berkeley to downtown San Francisco. This was before I was familiar with the effects of Dextromethorphan; a hallucinatory dissociative that’s in many commercial cough medications. By the time I exited the BART, I was cross-eyed and painless; relaxed and floating; and my mind was… lucid — full of thoughts and quips about neopsychedelia and the magazine and the oncoming event.

I was damn good, if I do say so… quick, self-amused (this annoying tendency actually tends to come off well on radio), and perhaps a bit too fearless. Krasny seemed to enjoy bantering with me about the perceived dangers of mass psychedelic use versus the wonders of a psychedelic movement and about politics and culture and whatever came up. My tongue and brain were loose and careless.

Then the phone lines opened up to callers. In between calls from people asking for drug advice and wanting to know details about the magazine and upcoming party, there were numerous angry calls from people upset that Krasny would even have this glib freak on his esteemed show advocating for psychedelic drugs and displaying bad attitude towards God, Mom, Apple Pie, and Patriotism (or whatever the hell I spoke about in my ripped and fevered mental state). Finally, just a few minutes before the show’s end, a man with a deep angry voice thundered across the airwaves, “Tell that asshole we’re gonna kill ‘im. We’re gonna shoot ‘im.â€Â Krasny fell into a rage. “Nobody makes death threats on my show! I’ve never had a death threat on my show!â€

Exiting the station to make the 4 block walk back to the BART, I was a bit less fearless, but, as I remember it, there weren’t even any cars rolling past as I made my way. And, anyway, on the radio, no one can tell what you look like. (And they couldn’t Google you yet.)

When I got back to her place, Alison exclaimed: “That was incredible!â€Â It was the first time she’d been thrilled by one of my public appearances; in fact, up until that point, I think she had her doubts about my mental dexterity. (Those doubts would occasionally reoccur, maybe deservedly so.) Anyway, that’s how I know that the whole thing didn’t just seem good to me because the Dextro was flooding my brain with Serotonin.

I was stunned the following Saturday as hundreds of paying customers — most of them young — flooded into The Farm for the event.

It was an incredible venue; large, with an upstairs section.

Scrappi DuChamp: I went to that. I was really fascinated by the place… It was an animal auction house… it was like an auction for slaughter, basically, of livestock, run by hippies. I thought that was pretty amazing. It was under a freeway or past a really old part of San Francisco that was still sort of undeveloped.

R.U. Sirius: Wavy was on and enthusiastic. The psychedelic drugs panel was colorful, as Zarkov, the libertarian investment banker, appearing in a dramatic disguise, denounced his fellow panelists for trying to get psychedelics sanctioned by the government for the exclusive use of psychotherapists. And we quietly passed out capsules with threshold doses of the still legal designer hallucinogen 2cb, which definitely added a cheerful intelligence and intensity to the affair…

… R.U. Sirius: The “Neopsychedelic renaissance†continued apace, with major features in High Times and other long forgotten zines, radio interviews and so on —with High Frontiers often touted as the reigning representation. It seemed that I was blabbing to someone in the media about it at least a couple of times a month. Soon word hit us that people on the L.A. garage psychedelia scene were being drenched in high quality LSD and were diggin’ on High Frontiers. Greg Shaw’s Bomp Magazine was at the center of that scene and he sent us his back issues (which we were already buying, anyway) and suggested we come for a visit. Jeff Mark and I arranged to go down there.

Jeff Mark: Winter Solstice 1985, R.U. and I took a trip to Los Angeles. The “Neopsychedelic Revival” was by then a real phenomenon. Tom Petty had released “Don’t Come Around Here No More”, including the Alice-in-Wonderland video — videos themselves were still new then, recall. Newsweek had even done a feature piece on the L.A. manifestation, focusing on Greg Shaw who was putting together some L.A. neopsychedelic ‘zine. R.U.’s intention was to make contact and build a bridge; the Pranksters’ visit to Millbrook, no doubt, in the back of his mind.

So we hung out for a while with Greg. I think we did a little sightseeing, and then that night we went to see some bands being promoted by him. The space the bands would play in, around the corner from Hollywood & Vine… well, you can’t call it a club. It wasn’t that, it was just… a room. The entrance was at the top of an external staircase, from which I could see underneath the building, noting with some trepidation that the second floor was supported by a bunch of those steel jacks that builders use to keep a weak ceiling from collapsing. And this would be holding up a couple of hundred dancing humans. I think this might even have qualified as an early form of rave, had that term yet been coined.

There were maybe four or five different bands, each doing 30-45 minutes or so, and the first thing I noticed was that, in keeping with the whole “Neo-Psychedelic Revival” thing, each of them did a version of “White Rabbit”. OK, that’s an exaggeration; one of them didn’t. The next thing I noticed was that the bands each seemed to be made up of the same seven or eight people in varying combinations of four or five.

So, anyway, the building didn’t collapse, and we retired after to some other location lost to history for a party. Everyone was high on MDMA, of course. As the evening progressed, I engaged in conversation with several very nice people, and by way of introducing each other, the usual “so what do you do?” kinds of questions arose. Now, I had a straight job at the time, civil service, thoroughly boring. But the people I spoke with described themselves as “make-up artists” or “costumers” or writers or artists of one flavor or another. I began to realize that vocationally, each of these people depended on all the others, networking (another not-yet-coined-term) to get to work on someone’s project about something; their livelihood depended on their social contacts.

Now, when you think about it, this was Hollywood; that’s how Hollywood works, that’s how creative communities, particularly those in collaborative crafts, operate. That’s how they produce. Obvious to many, but news to me. The pattern-recognition subsystems of my mind began to assemble what I would come to call my “Theory of Scenes”.

A few months later we returned, with Lord Nose, to participate in this event that featured a couple of local bands, and somebody wheeling out Sky Saxon from the Seeds (“Pushing Too Hard”).

Nose was showcasing these black t-shirts with the yellow day-glo anti-happy face or whatever the fuck that was (I still have mine, but it no longer fits…) (ed: Sacred Cow Mutilators t-shirt). And it struck me that the 200 or so people at that event, which included almost everyone we’d met in December, comprised the whole of the “neopsychedelic scene” in L.A. That was it. That was all of them. 250 people tops, and they were getting all this media attention. And I realized that’s how it probably was in ’65, as well; there was the Whiskey á Go-Go scene, one or two other places; a dozen or so bands with some duplication among their personnel, various friends and hangers-on. In the Haight, the same thing. There was the Fillmore, and the Matrix, the Diggers, the Oracle, and it was all the same… what, 300 people? It applies elsewhere also. There’s the NYC comedy scene (which in the 70s gave us SNL, and is now focused around The Daily Show), the Boston Harvard/National Lampoon scene, the L.A. Conception Corporation scene (whence came Spinal Tap). All of these basically, at least in the beginning, were not much more than groups of friends. Even in politics. One of my disappointments as I’ve gotten more sophisticated about politics is the realization that so much of what happens in a place like Washington D.C. takes place in what appears, anyway, to be a social environment, which is why it reminds us so much of high school. And this was, largely, how “Mondo†functioned within the context of the Berkeley New Age “Scene”.

R.U. Sirius: Greg Shaw and this guy from a band called Dead Hippie volunteered to throw a High Frontiers party in L.A. so we went back down there a few months later. The Dead Hippie guy was intense. He had sort of a Charlie Manson look and a stare to match and seemed to be searching for some sort of gut wrenching apocalyptic truth. Other that that, he was nice. We hung out for a while as the party was being set up until it became clear that we had no responsibilities other than to man our booth, sell magazines and t-shirts and take home some money.

One peculiar memory: we split for a while for dinner and drinks and somehow struck up a conversation with this crewcut military-looking young dude. When we told him what we were in town for, he tried to convince us to ditch the benefit show because it would be more interesting to drop acid and play paintball at some arena a few miles away. It was his favorite thing.

As with the “Cotilllion,†the L.A. High Frontiers benefit was massive, with bands like Thelonious Monster (I was already a fan) and members of Black Flag who were doing this sort of metal psych as a side project. Sky Saxon jumped on stage with everybody. This being L.A., everybody looked perfect, particularly the young girls in their tight short skirts. After hours of watching hundreds of these chicks stream though, the massive doorman/bouncer finally cried out, “I’ve got a sheet of acid for the first chick who will drain my cock.â€Â I seem to remember him being approached by a volunteer.

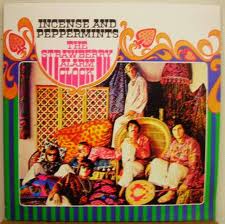

I really didn’t connect with anybody other than one porn star-gorgeous chick I’d met the last time around, and her attention was divided between myself and several others taller, darker and more handsome. It was a whole different vibe, not only from the San Francisco party but from the previous hangout in L.A., which had more of a gently androgynous fashion-y pop vibe — all retro Nehru shirts and flared striped pants. Now the scene had become psych metal. They’d gone from Strawberry Alarm Clark to Blue Cheer in a matter of weeks.

Previous MONDO History Entries